2014 marks 100 years since the start of World War I. Libraries and archives around the globe have begun to highlight and share material from their collections to further the study of the war which resulted in 37 million military and civilian casualties.

Within six weeks of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Europe would be engulfed in war. The assassination took place in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, 100 years ago this coming Saturday.

At the Brooklyn College Archives, we have a folder containing World War I photographs and documents belonging to the eminent psychologist Dr. Paul Shilder (1886-1940). Schilder served in the Austro-Hungarian army and later immigrated to the United States where he met and married his second wife Lauretta Bender, whose papers we have at the College.

Schilder graduated from the University of Vienna’s Medical School in 1909. He volunteered for military service at the beginning of the war and served at the front and in army hospitals. During the war, he received a doctorate in philosophy, often studying while under heavy gunfire.1

The ill-equipped Austrian medical corp was overwhelmed by the large numbers of casualties and in 1916 possessed only 2 doctors for every 1000 soldiers. The army even resorted to promoting men with four semesters of medical training to the rank of Medical Lieutenant.2

Most of the photographs we found are of Schilder stationed along the front in Poland. In 1914, Poland did not exist as a sovereign state and its territory was split between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Major battles fought in this area include the battles of Gumbinnen and Tannenberg in 1914.

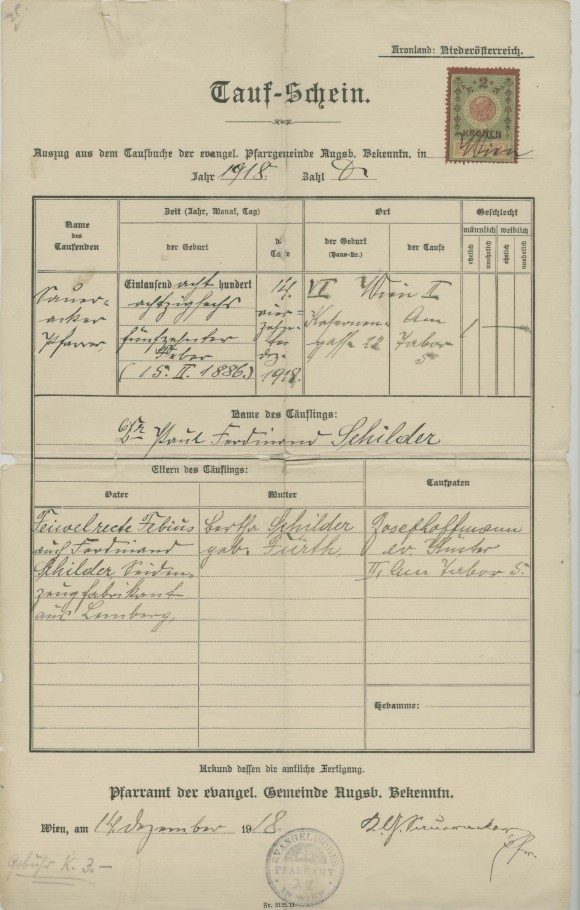

Toward the end of the war, Schilder was wounded and sent to recover in the Tyrol region of Austria where he met and fell in love with Mitzu, the daughter of a local innkeeper. Since it was illegal for people of different faiths to marry in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Schilder who was Jewish, converted to Protestantism in order to marry Mitzu.3

In the Lauretta Bender Papers, we found Schilder’s certificate of baptism, issued before his wedding to Mitzu.

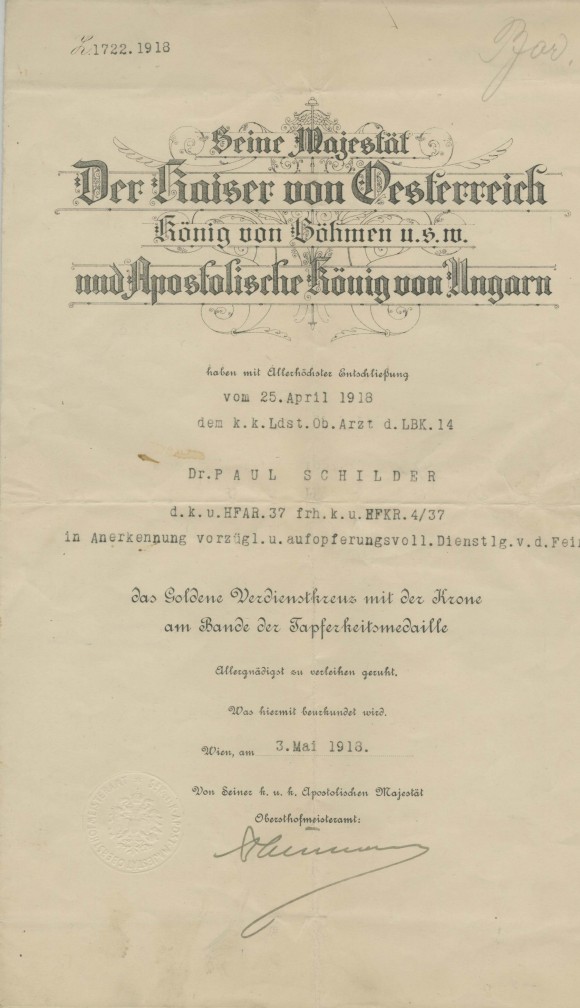

We also uncovered a document detailing the medal awarded to Schilder for bravery on April 25, 1918. At the top of the document the official title of Charles I, the last ruler of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, appears: Seine Majestat Kaiser von Österreich, König von Böhmen u. s. w. und Apostolischer König von Ungarn (His Majesty the Emperor of Austria, King of Bohemia, etc. and Apostolic King of Hungary).

After the war Schilder joined the staff of the University Hospital in Vienna and worked there under Dr. Wagner von Jauregg until 1929. During this time, Schilder met Freud and joined the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Schilder became acquainted with Lauretta Bender in 1930 when he was a visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. He recieved his US citizenship in 1930 and married Bender in 1936. Since there very few documents in the collection related to Mitzu, we do not know when his first marriage ended. Schilder and Bender lived in NY where he became the director of clinical psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital and an associate professor of psychiatry at New York University. He and Bender often collaborated and supported each other’s research efforts.

At the time of his death in 1940, Schilder, who is best known for his ideas on body image and group therapy, was working on a global outline for psychiatry. He also established the Schilder Society (1935-1981) as a forum to exchange ideas on psychotherapy.

Explore World War I on the Web

A wonderful example of library cooperation and sharing is the website Europeana 1914-1918 which contains archival documents, photographs, and film from 10 state libraries. Individuals can participate in this archival initiative by uploading their own documents chronicling the Great War.

Further Reading

Nonfiction

Shaskin, Donald and William Roller, eds. Paul Schilder Mind Explorer. New York: Human Sciences Press, Inc, 1985.

Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918. London: Arnold, 1997.

Literature

Barker, Pat. Regeneration. New York: Plume, 1991.

Hasek, Jaroslav. The Good Solider Schweik. New York: Penguin Books Limited, 1939.

Hill, Reginald. No Man’s Land. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Kendall, Tim, ed. Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Remarque, Erich Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front. Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1929.

Endnotes

1 “Vita of Paul Schilder,” in Paul Schilder Mind Explorer, eds. Donald Shaskin and William Roller (New York: Human Sciences Press,1985), 268.

2 Holger H. Herwig, The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918 (London: Arnold, 1997), 301.

3 Sam Parker, “Refelctions on Paul Schilder,” in Paul Schilder Mind Explorer, eds. Donald Shaskin and William Roller (New York: Human Sciences Press,1985), 23.

My nephew’s name is Paul Schilder. Is he related to Paul Schilder from your article?